Weston’s Humberstone Walls

An enduring legacy

Weston’s beautiful Humberstone walls are something of an enigma. They can be found throughout our Village and in many ways help define it. They lend a warmth and old-world charm to our neighbourhood; moreover they elicit admiration for their clever construction and imaginative design. They are a remarkable legacy. Yet, surprisingly, the story of how they came to be created, and by whom, has all but faded from our collective memory.

Springmount Avenue, Weston - Photo by Janet Fahey

That is, until now. In a remarkable sequence of events, described by one resident as a “perfect alignment of the stars”, the clouded past has been swept aside, allowing us an unparalleled opportunity to examine this important aspect of Weston’s history. Our serendipitous journey began in September 2008 when a section of Humberstone wall on Joseph Street was destroyed, raising an outcry among residents. This prompted Cherri Hurst, president of the Weston Heritage Conservation District, to begin extensive research into the walls in an effort to raise community awareness. She verified that James Gilbert Gove, a master stone mason, was principally responsible for the construction of the walls and that he was aided by longtime Weston resident Charlie Gillis.

During the course of Cherri’s research, we were surprised to receive an email from Dr. John Carbone, a resident of Virginia. Dr. Carbone, the grandson of James Gove, had seen our website and wanted us to know that he had been working with Dr. Gary Miedema of Heritage Toronto, to obtain authorization for an official plaque honoring his grandfather’s work in Weston. Dr. Carbone and his family provided us with a rich depository of photographs and stories concerning James Gove and Charlie Gillis.

Combining this inspiring resource with her own extensive research, Cherri wrote a wonderful article detailing the history of Weston’s Humberstone walls, entitled “Stories in Stone”.

Stories in Stone

By Cherri Hurst

|

Fern Avenue, Weston - Photo by Phil Keirstead

|

What do you see when you look at the stone work around Weston? Do you see the incredible forces it took to shape the rocks millions of years ago? Can you visualize the stone mason contemplating which stone will fit exactly where it is needed? Are you able to picture an old man slowly leading his beloved horse and wagon, laden with stones, out of the Humber valley?

There are as many stories about the stonework as there are stone walls in Weston. Each time something gets torn down, we lose not only the fence and the stone, we also lose the stories.

|

THE STORY OF JAMES GILBERT GOVE

Building stone walls like the ones we have in Weston was a time consuming, meticulous and physically demanding job. No one knows who built all of them but we do know that master stone mason James Gilbert Gove spent almost forty years in Weston creating a great many of them.

|

James Gove was born on December 20, 1884 in the village of Holcombe Burnell, Devon, in the southwest of England. As a young man, he apprenticed as a stonemason and when his training was complete, he began working in the building trades in Devon and neighbouring shires.

During World War I, Gove served in the 505th field company of Royal Engineers. His unit shipped out at Christmas 1916 and once in France, was sent to engage in some of the bloodiest fighting of the war, including clashes at Passchendaele and the Allied assaults on the Hindenburg Line. For his service, Gove was awarded both the British War Medal and Victory Medal. He returned to England in March 1919.

After the war, with a wife and three children to support, Gove decided to move to Canada to seek employment and a better life for his family. He departed England in April 1924, arriving at the port of Halifax and shortly thereafter, made his way to Weston. His wife, Ida, and his family followed thirteen months later. By the time their fourth child was born, in 1929, they were living in a lovely home at 152 North Main Street (later renumbered 2104 Weston Road) near the corner of Fern Avenue. Gove immediately became active in the community, joining the Royal Canadian Legion and Sons of England Fraternal and Benefit Society.

|

James and Ida Woodberry Gove

with daughters Laura and Irene

Circa 1916

Photo courtesy of Gove family

|

|

Gove working on Dr. Charlton’s house

at the corner of King Street Crescent and Weston Road

|

During this time, Gove began to plan and construct numerous river stone walls for neighbouring properties and for the municipality of Weston. These walls were made from brown siltstone brought up from the Humber River and were distinctively designed, similar to walls in Devon and Somerset, capped with upright narrow stones and often held in place by short flanking pillars. Gove was responsible for many walls fronting Weston Road, Fern Avenue and Lawrence Avenue, as well as those along King Street Crescent and Little Avenue.

Photos of James Gove and WCI courtesy of Gove family

At the outbreak of WWII, Gove again wanted to enlist in the army but at the age of fifty-five, he was deemed too old for front line duty. Instead he served as a guard at the Massey-Harris ordnance plant in Weston.

|

|

|

|

|

Gove built the wall on the campus of the newly expanded Weston Collegiate Institute in the 1950’s

|

Photo courtesy of Weston Historical Society

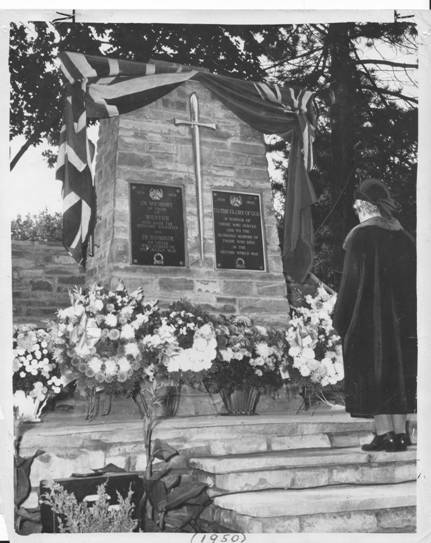

In September of 1949 there appeared in the Times and Guide an artist’s conception of the proposed new war cenotaph that the town council had decided to build. It was to replace the old memorial that was “variously described as unattractive, neglected and broken down”. Designed by Mr. James Shaw, “the actual stone work in dismantling of the cairn and erection of the new memorial was carried out by a well-known Weston resident, Mr. James Gove... The completed memorial is something of which all Weston citizens must be very proud of and to the creator and constructor must go the great satisfaction of a job well done.”

The plaque and stone from the original cairn were embedded in the construction of the new memorial.

Gove completed this labour of love in time for its dedication to the community on October 5, 1950. Hundreds of people came out to the unveiling. The cenotaph still stands today as a memorial to the people who gave their lives in both World Wars but also as a tribute to the man who put his heart and soul into his work.

James Gove worked as a stone mason for the rest of his working life in and around Weston. As late as 1951, the Town Council minutes state “that the Parks Committee is hereby authorized to engage Mr. James Gove to erect a stone fence adjoining the south boundary of the Town Hall Park at an approximate cost of $400.00.”

Photo by Cherri Hurst

“The job of stone mason is not an easy trade since in building stones one must break the larger stones with a sledge hammer to the desired size. This is not easy to do and then some artistic ability is required to put the colours and sizes in a pleasing arrangement. The pattern of light and dark stones is important.”

-Gil Gove (son of James Gove)

Mark of the stone mason’s hammer

“From early childhood and through my teen years, I have a clear recollection of my father leaving the house in early morning, bound for a stone-work project somewhere in Weston. He did chimneys and walkways to mention some, but particularly enjoyed constructing walls and did many around the town. He took great pride in his work and spent long hours to make his work reflect his high standards. After the war ended, he resumed stone building and then the cenotaph project was born and he was very excited about having this opportunity to contribute and also exhibit his skill. He would leave our house by 8 a.m. and walk the mile to the cenotaph site. I remember his conversations with a colleague about preparation and design. He would return at dinner time, dusty and tired but pleased with his work and pleased to see the cenotaph taking shape. He could have walked home for lunch but rather took a sandwich with him so that he could eat it while sitting and looking at the work to be sure that it was progressing well....”

-Jean Gove Carbone (daughter of James Gove)

Photo of Jim Gove, age 2, at Weston Cenotaph - courtesy of Gove family

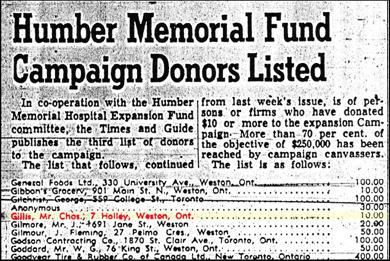

THE STORY OF CHARLES GILLIS

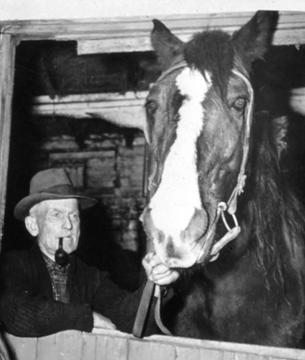

The pride, creativity and sheer physical labour that James Gove put into his work are only part of this story. How did he get the rocks he used from the river? Who loaded and carted them to the work sites? Up until the mid 1950’s, he relied on a teamster named Charlie Gillis. Charlie’s story begins when he was born in 1878. He seems to have come to Weston about 1913. The town’s Auditor’s Report for that year shows them buying gravel from Charlie for $11.25. He lived alone in a rented log cabin on the edge of the Holley estate and managed to make his living hauling, moving and loading anything that anyone wanted. He mowed the grass in Cruickshank Park, moved houses when Main Street was widened and boarded the town’s horses in his stables.

|

Charlie Gillis did well enough to take out an ad in the Weston Times and Guide that continued to run for many years. He brought the stone from the river at 75 cents per load. In 1925, at the age of 52, he bought that little cabin on Holley Avenue. Ten years later he purchased a building on the corner of John and Jane Streets for $40.00. He must have stretched his finances a bit, but by 1939 he was out of arrears never to have that trouble again.

|

“When I was a kid playing down by the river in the 1930s, it was a common sight to see Charlie, his two horses and his old wagon right out in the middle of the river. Charlie would be standing in the water too and searching for stones of the right size that he would then heave up into the back of the wagon. The water was not deep when Charlie was doing this – 18 or 20 inches at most – and when he had enough of a load to make the trip worth his while but not too much for the horses to pull, he would leave and make the delivery to my father. Charlie lived alone in a small house nearby. Charlie, back then, was not young. He had a beard that covered his neck and the top of his chest. The hair on the top of his head was thinning but was long and not cut, and it came down well past his ears. He was always dressed in very well-worn clothes and wore big heavy work boots. That was Charlie.”

- Jean Gove Carbone, daughter of James Gove |

Photo courtesy of Weston Historical Society |

Charlie was obviously a worker and willing to do what he could to make ends meet. He never married and if he had any family they did not stay in Weston long. He was still working in 1948, at the age of 70, when Council “engaged (Gillis) to move…buildings (from Main Street) for the sum of $150.00 each.”

Charlie was obviously a worker and willing to do what he could to make ends meet. He never married and if he had any family they did not stay in Weston long. He was still working in 1948, at the age of 70, when Council “engaged (Gillis) to move…buildings (from Main Street) for the sum of $150.00 each.”

THE GEOLOGICAL STORY OF WESTON’S HUMBERSTONE WALLS

The tales of Charlie Gillis and James Gove are incomplete without knowing the stories of the rocks that gave them their livelihoods.

The origin of the flat, brown river stone:

Weston has a lot of history behind it but who would have thought that some of it started 445 million years ago? At that time, Weston, and in fact all of Southern Ontario was flooded by interior seas. Weston existed in a Bahamas-like climate with many hurricanes howling over the area. Rivers and streams carried worn rock particles great distances, depositing them in the sea to create large deltas of sand, silt and mud. Volcanoes heaped ash layers on the sea floors. All of these materials became compacted by enormous weight and pressure and cemented together, like pages of a book, to form sedimentary rock. These rocks contain fossils of marine organisms such as trilobites, gastropods and brachiopods. The stone that was created from these forces is now preserved as the shale and silty limestone layers of the Georgian Bay Formation. These are the rocks that Charlie Gillis harvested and James Gove used to make his beloved walls.

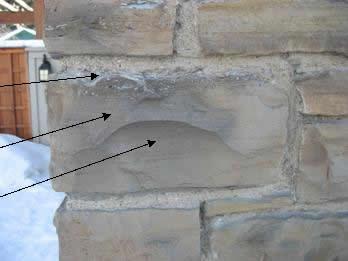

Rocks tell their own stories; the section of river stone pictured at the right shows the different stages of its formation.

Rocks tell their own stories; the section of river stone pictured at the right shows the different stages of its formation.

This layer came from the era of warmer, tropical seas teeming with lots of plants, trilobites and gastropods

This part originated in deeper oceans with no life in them

Note the layers of sediment that eventually hardened into rock

Photos by Cherri Hurst

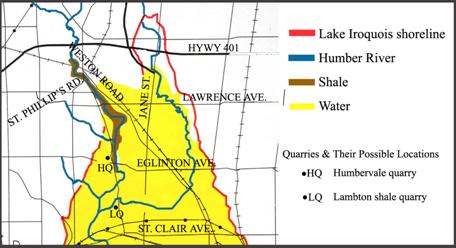

The Humber River Valley is a product of glacial action and water drainage which, over tens of thousands of years, carved through the shale layers of the Georgian Bay Formation to form a wide trough. Further erosion of the valley, caused by the fast moving Humber River, has exposed large sections of this soft sedimentary stone in the Weston area. “Humberstone”, thought to be the name given to any stone from the harder siltstone layers near the Humber River, can no longer be obtained for building or for personal use. Mining the river is now prohibited.

The Humber River Valley is a product of glacial action and water drainage which, over tens of thousands of years, carved through the shale layers of the Georgian Bay Formation to form a wide trough. Further erosion of the valley, caused by the fast moving Humber River, has exposed large sections of this soft sedimentary stone in the Weston area. “Humberstone”, thought to be the name given to any stone from the harder siltstone layers near the Humber River, can no longer be obtained for building or for personal use. Mining the river is now prohibited.

The creation of quarries in the Town of Weston was never allowed, so it is possible that some of the stone in our buildings and elsewhere was transported from quarries outside the area, possibly the old Lambton Shale pit or the Humbervale quarry. Neither of these quarries exists today.

The creation of quarries in the Town of Weston was never allowed, so it is possible that some of the stone in our buildings and elsewhere was transported from quarries outside the area, possibly the old Lambton Shale pit or the Humbervale quarry. Neither of these quarries exists today.

Humber embankment, circa 1950. Note the layers of sedimentary rock that have been exposed by erosion.

Photo courtesy of Weston Historical Society

The origin of the rounded stones and boulders:

Not all the stone in Weston’s walls and fences came from the Humber River. Thousands of years ago, this area went through a series of ice ages where the land was covered and uncovered by massive glaciers advancing and retreating. The last of these continent-wide ice sheets was the Wisconsin glacier. Some 13,000 years ago, as the glacier receded for the last time, it did so unevenly with the north eastern end of Lake Ontario being blocked by ice. Inflowing rivers and melt water from the ice could not escape and the water level rose to create Lake Iroquois, which drained through the Mohawk and Hudson River valleys to the ocean. Its shoreline stretched as far north as Weston and was responsible for depositing vast quantities of sand, gravel and clay in this area.

Not all the stone in Weston’s walls and fences came from the Humber River. Thousands of years ago, this area went through a series of ice ages where the land was covered and uncovered by massive glaciers advancing and retreating. The last of these continent-wide ice sheets was the Wisconsin glacier. Some 13,000 years ago, as the glacier receded for the last time, it did so unevenly with the north eastern end of Lake Ontario being blocked by ice. Inflowing rivers and melt water from the ice could not escape and the water level rose to create Lake Iroquois, which drained through the Mohawk and Hudson River valleys to the ocean. Its shoreline stretched as far north as Weston and was responsible for depositing vast quantities of sand, gravel and clay in this area.

Eventually, as the ice dam melted, Lake Iroquois found a new outlet, draining rapidly eastward through the St. Lawrence Valley until the water and shoreline dropped to what we now know as Lake Ontario.

Eventually, as the ice dam melted, Lake Iroquois found a new outlet, draining rapidly eastward through the St. Lawrence Valley until the water and shoreline dropped to what we now know as Lake Ontario.

The receding water left behind a vast quantity of Halton Till (a jumble of rock fragments ranging in size from silt to boulders, many originating in the Canadian Shield).

This material was used by the future settlers of Weston to build their homes and foundations and is the probable source of the round boulders that cap many of Weston’s Humberstone walls and fences.

LEARNING FROM OUR LONG, STORIED PAST

The stories of James Gove, Charlie Gillis and Weston’s Humberstone bring our walls to life and make us realize that there is more to these creations than just stone and mortar. They tell of times gone by, pride in workmanship, and finite resources no longer available. Although each wall is unique, together they connect us as a community. The next time you are frustrated with those old stones or worried about the cost of restoring a wall, think of everything that has gone into them. Please, give them the happy ending they deserve.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are deeply grateful to Dr. John Carbone, James Gove’s grandson, who supplied a great deal of the biographical information for the Gove article. We also wish to thank Jean Gove Carbone and Gilbert Gove, James Gove’s children, for the wonderful first-hand accounts of their father and of Charlie Gillis.

We are also indebted to Ed Freeman, a local geologist and member of the Geological Association of Canada, who helped Cherri interpret Weston’s geology and provided technical input for this article.

Springmount Avenue, Weston - Photo by Janet Fahey